Product

3D Personas for Complete Customers Insights

Summary

“In this age of the customer, the only sustainable competitive advantage is knowledge of and engagement with customers.” — Forrester Research

Introduction

Over the last few years, user personas have been widely accepted as the way to represent the voice of user/customer. Alan Cooper introduced the concept of user personas for software design in early 1980s. Cooper provided general characteristics of user personas and recommended that software should be designed for single archetypal user. In the 1990s, Angus Jenkinson working with Ogilvy extended the concept to use it for brand marketing activities. Jenkinson & Ogilvy’s approach was to use persona to capture the essence of the “tribe of people who share affinity with the brand’s values”; towards this, they started including a prototypical character along with its fictional identify, values, behaviors and attitudes. More recently, persona has been adopted for online marketing purposes and this incarnation is referred to as the “buyer persona”. This variant captures buyers’ needs and context and enables marketing teams to match buyers’ requirements during their buying journey.

Putting a relatable human face to an otherwise abstract representation about users (know as “user segments” or “target audience”) helped product and tech teams to think build better products by identifying and prioritizing more relevant use-cases. Using personas has been shown to be beneficial: 82% companies using personas improved their value proposition and were able to communicate their value more effectively. Research shows that B2B marketers who use buyer personas are 4 times more likely to meet and exceed their goals. [link] As a result, an increasing number of teams are now beginning to use personas to guide their product development and marketing roadmaps.

Though personas adoption is increasing, unfortunately, product and marketing teams within a company end up building separate, siloed versions of personas. Moreover, though Jenkinson & Ogilvy used the personas for brand marketing, there are no well-defined guidelines for incorporating brand-related details in the persona definition (besides capturing high-level values, attitudes, and user’s context, i.e.).

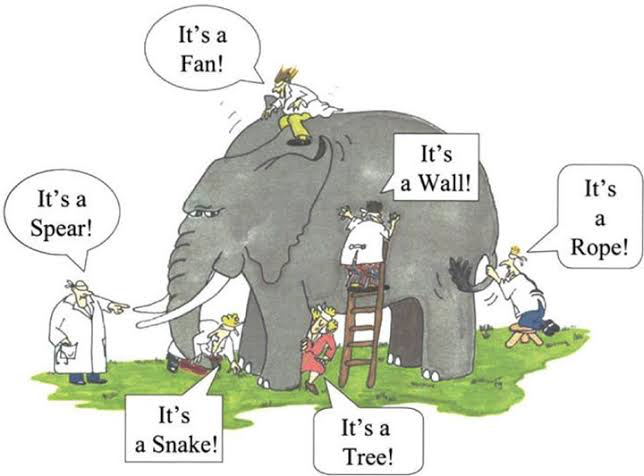

This has resulted in the challenge faced by the “blind men” describing the “elephant” based on their limited perspective; each one of them was right but no one had the full, all-around perspective and, therefore, were not able to understand the object completely and correctly.

We see a similar challenge with personas: each team has a correct but incomplete picture of their users and, as a result, the organization fails to derive full and deep insights about their users. There is a need to define a common and shared persona across different teams to build a complete three-dimensional view of users — a view that provides 360 degree perspective to all teams within the organization.

Customer Journey

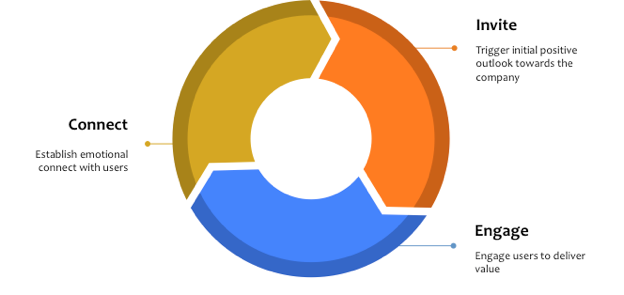

A customer’s journey with any product has three phases: Invite, Engage, and Connect. This is true for any kind of product — digital products (such as consumer products or business SaaS products for small/large enterprises) as well as non-digital products (such as cars, apparel, fashion, entertainment, etc.).

In the Invite phase, customer explores the product to evaluate if value proposition offered by the product resonates with them. In the next phase, customers Engage with the product (before and after conversion/purchase) to derive value from the product. If the product delivers the promised value, customers start developing an association with the product — which, after repeated and consistent value delivery by the product, evolves into emotional Connect with the product (that often transcends the functional attributes of the product).

Company building a product or service has to cater to these three phases of customer journey in a distinct manner. During the Invite phase, the company needs to trigger initial positive outlook towards the product amongst the right sets of users and ensure that the users have good initial experience with the product. During the Engage phase, company needs to ensure that users have a good experience (both before and after value delivery). Finally, during the Connect phase, company needs to proactively work towards establishing emotional connect with the users.

The figure above shows customer journey as a loop with Invite phase leading to Engage phase and Engage phase leading to Connect phase. The figure also shows Connect phase leading back to Invite phase. Why should this be the case? This is because happy and emotionally connected users inevitably talk about a newly discovered product/service with their family members, friends and colleagues. Also, thanks to social networks and influence networks (social media, e.g.), the word-of-mouth buzz spreads wider and persists longer. These digital footprints left by users, therefore, help to improve the Invite for the next set of users.

Since every iteration helps improve subsequent iterations, customer journey is not merely a loop, it is better represented as a “spiral” that keeps improving and growing bigger as the products goes through Invite — Engage — Connect phases with every customer.

3D Personas

Given that Invite — Engage — Connect phases correspond to three different stages of customer’s journey with the product / company, we can appreciate that customers have different outlooks during these three phases. For example, users typically want to explore broadly without much effort during the Invite phase of customer journey. Users are typically more specific and particular during the Engage phase on customer journey. After users have experienced consistent value delivery from the product, they become more open and accommodative during the Connect phase of customer journey.

Based on this insight, we have learnt that it is useful to look at personas from three different dimensions corresponding to the three phases of customer journey:

1. Invite dimension

2. Engage dimension

3. Connect dimension

We will provide an overview of each of these dimensions below. At a high level, Engage dimension corresponds to users’ functional needs while Connect dimension corresponds to users’ higher-order non-functional goals. In this context, the Invite dimension corresponds to making users aware that their “problems” (which can be needs or goals) have a solution.

Since we have used the terms “functional needs” and “non-functional goals” above, let’s look at them a bit closely. William Powers proposed “The Extended Phenotype” model that considers human beings to be a hierarchy of control systems — where each control system senses something in the environment and tries to control (respond to) the stimulus. Powers defines hierarchy of control systems as follows:

In other words, human beings have a hierarchy of goals. This hierarchy of goals is what drives people to perform different activities. Based on this, functional needs correspond to the “Do Goals” while non-functional goals correspond to the “Be Goals”.

Klement explains these as follows [link]:

Your ideal self is a synthesis of various Principles or Be Goals. For example, you think of yourself as a particular type of parent or friend and having a particular set of personal freedoms. These Be Goals are what motivate you to choose and carry out one or more Programs or Do Goals. These Do Goals are then fulfilled by a sequence of activities or tasks (or Motor Control Goals).

Be Goals have the highest priority; Motor Control Goals have the lowest. Be Goals are the core drivers of all our actions and decisions. This also means that, no matter how well a Do Goal or Motor Control Goal is fulfilled, it’s a failure if the higher Be Goal is not satisfied. It also means that a Do Goal doesn’t have to be successfully executed to fulfill a Be Goal.

Do Goals are characterized by Leo McGinneva’s famous clarification about why people buy quarter-inch drill bits: ”They don’t want quarter-inch bits. They want quarter-inch holes.”

Be Goals are characterized by Charles Revson’s explanation about the business of Revlon, Inc.: “In the factories we make cosmetics. In the drugs stores we sell hope.” Be Goals are the most stable because they are the states of self-perception (which, incidentally, depend (to a certain extent) on the life stage of the person). Be Goals also depends on person’s context and his/her environment — where they live, where they work, what they do, etc. In other words, Be Goals are non-functional and entirely emotional. On the other hand, Do Goals are purely functional and correspond to the activities that a person does to fulfill a Be Goal.

With this context, we now discuss each of these dimensions in the following order: Engage dimension, Connect dimension, and Invite dimension.

Engage dimension

Engage dimension corresponds to the stages that starts after customer has experienced value in some initial form and includes not only the final value delivery but also repeated value consumption (either in the form of retention or repeats).

Since the Engage phase of customer journey corresponds to the stage where the users are actively using the product, Engage dimension primarily corresponds to the functional usage of the product. Engage dimension, therefore, relies on Jobs-As-Activities aspect of the JTBD. Anthony Ulwick is the primary proponent of the idea of Jobs-As-Activities [link]. Ulwick defines JTBD as:

A task, goal or objective a person is trying to accomplish or a problem they are trying to resolve. A job can be functional, emotional or associated with product consumption (consumption chain jobs).

JTBD provides a framework for (i) categorizing, defining, capturing, and organizing all your customer’s needs, and (ii) tying performance metrics (in the form of desired outcome statements) to the JTBD.

Examples of “jobs” in this model include taking a cab to travel to office, listening to music, and getting food delivered to one’s home. As a result, the activity becomes the fundamental unit of analysis. Any emotional considerations are secondary to this core, functional job.

Of course, while defining JTBD, one has to be mindful about user’s needs and not be centered on the product itself. For example, one has to consider alternatives that are serving the same purpose but in a very different form. For example, competitors of a music-streaming app are not only other music-streaming apps but also various entertainment options that can help users relax and recharge.

An important aspect of the Engage dimension that plays a big role in product adoption is the natural frequency of the activity. Natural frequency of usage corresponds to how often users do a specific activity in the natural setting (i.e., either by using company’s products or otherwise). The totality of user’s activities related to a specific category provides natural frequency for that category. Note that the natural frequency is not related to how often users are using company’s product; it is the natural frequency of the activity in users’ life. Frequency of usage is useful because it provides an overview of user’s overall needs.

For example, for urban mobility, we can calculate natural frequency of usage by understanding different forms of transportation needs of an user: user might be commuting between home and office 10 times a week (i.e., twice a day during weekdays); between home and exercise place (such as a gym) 6 times per week; 5–6 times per week between home and retail stores for errands; 2–3 times between office and restaurants; etc.

Frequency of usage (of each activity) plays an important role not only on product and process design but also on the monetization options available to the startups.

A closely related concept is effort required to do the activity and user’s motivation and ability to perform the activity. Higher the usage frequency, higher is user’s desire to perform such activities with lower overheads. In other words, higher frequency tasks place higher premium on convenience and reward products/services that offer better UX with lower effort requirement.

Adoption and usage of a product depends on target user’s/customer’s tech awareness and comfort. For tech-driven products, customer’s tech outlook (i.e., whether they think they can use technology to solve their problems) plays a crucial role. Initial customers are typically tech optimists — customers who are willing to explore newer approaches to solve their problems.

To summarize, Engage dimension focuses on the following aspects of users:

- JTBD — users’ functional (esp. un-served or under-served) needs

- Natural frequency of activities (and effort required to handle them)

- Adoption readiness (tech optimism, etc.): helps figure out effort required to acquire and onboard customers

Engage dimension not only influences company’s product design and development but can also be used to improve company’s marketing activities.

Connect dimension

A number of activities people do (and, in fact, a lot of the things people buy) are related to their “wants” and not “needs”. These wants are tied to the person’s identity: people do things and buy things because the act of doing or buying not only fulfills their functional needs but, more importantly, helps them progress towards their non-functional wants. In other words, companies that people use (or the brands that people associate with) are — directly or indirectly (i.e., consciously or sub-consciously) — linked to what people want to be.

We refer to the non-functional wants of users as “Goals To Be Achieved” (GTBA). The dimension that focuses on the goals and unmet non-functional wants of users is referred to as the “Connect dimension”. This is in contrast with the Engage dimension that ignores non-functional and emotional considerations (such as user’s emotional outlook, attitudes, demographics, or psychographics) and focuses on functional jobs/tasks instead.

What is a good way to define GTBA? Since users can have a wide variety of non-functional goals, how can startups work with them? As per research done by a consumer intelligence company (that focuses on establishing emotional connection with users), there are “more than 300 emotional motivators” [link]. How can startups deal with these hundreds of emotional motivators and identify the key motivators?

We present a simple schema (inspired by the brand archetype wheel) that can be used by startups to get a handle on the emotional and non-functional goals. It can be used to group GTBAs into a handful of top-level clusters. The schema relies on two dimensions: emotional wants and functional needs. We define a 2 x 2 matrix of these two (with low and high value of importance along both the dimensions) to identify four distinct clusters of GTBAs. These four are represented as follows:

Let’s consider a few examples — both to understand which quadrant do various activities fall into and to explore the insights provided by GTBAs:

1. Low emotional importance + Low functional importance = freedom and independence; this quadrant corresponds to activities that are considered as “utilities” by users. Typically, users want to do things more efficiently (better, faster, cheaper, simpler, etc.) with the help of products/services in this cluster so that they have time for other “more important” goals in their lives. Examples of these are mobility and transportation services, digital payments, household services, productivity products (calendaring app, note taking app, etc.), etc.

2. Low emotional importance + High functional importance = challenges and achievements; this quadrant corresponds to activities that are either considered as important skills by users or considered as necessary (but not overly important) part of their lives. Examples of these are internet access, ordering food (to save time), business travel, and daily professional activities (catered to by SaaS products such as ERP, CRM, marketing automation, etc.).

3. High emotional importance + Low functional importance = stability and structure; this quadrant corresponds to activities that are considered an important part of their lives by users. Examples are health (as well as wellness and personal care related activities), finance-related activities, K12 education, real estate activities, etc. In addition, activities that help project one’s personality (and, therefore, aligned with one’s Be Goals). This is catered to by brands from non-functional categories such as fashion (apparel, jewelry, etc.) as well as gadgets, cars, hospitality, entertainment and media, etc.

4. High emotional importance + Low functional importance = connection and belonging; this quadrant corresponds to activities that help users connect back with their support groups (from nuclear families to the whole humanity). Examples are social networks as well as various activities that provide “experiences” or help enrich/deepen social connections — such as experiential hospitality provided by AirBnB, social e-commerce supported by PinDuoDuo, etc. This quadrant also includes activities such as movies, music, and events.

The above are indicative classification of a few activities. Note that it is possible that an activity might belong to multiple quadrants — in fact, a lot of innovation centers on entrepreneurs reimagining an activity to belong to different quadrant!

For example, in the hospitality sector, lower-end hostels (typically, hostels used by backpackers) as well as Bed & Breakfast properties occupy the “Challenge and Achievement” quadrant. On the other end of the spectrum, there are higher-end hotels and resorts, which focus on convenience and, therefore, occupy the “Stability and Structure” quadrant. AirBnB, ingeniously, figured out how the hospitality category can also belong to the “Connection and Belonging” quadrant! At the same time, we can see that typical AirBnB properties do not appeal to users who are seeking “Stability and Structure” — for example, business travelers or leisure travelers looking for luxury and pampering (with buffet meals, room delivery, etc.) during their vacation.

If a company understands its target users deeply, it will be able to build products that resonate deeply with their target users. If a company builds products that resonate deeply with users, it is also possible to get users directly involved in the products.

Towards this, products can be enriched to enable users to get involved with the companies during different phases of the customer journey. Besides making it easier for users to invite other users who might benefit from the product, products can be evolved to seek and capture user’s feedback — both about the product/service as well as ratings/reviews about the service providers. These interactions can be used to not only to improve customer’s engagement with the product but also to improve the experience of future users. And, of course, product can get super users (who are deeply connected with the product/service) to participate and contribute towards deepening emotional connect with other users.

Besides depth of emotional connect, user’s involvement also depends on user’s time and social outlook (which, in turn, depends on user’s life-stage). For examples, users in college versus in their first job behave very differently; likewise, users who have kids behave differently from users who don’t have kids. Corresponding to user’s social outlook and life-stage, appropriate effort has to be undertaken to reduce the friction and to minimize the effort. We refer to various factors that impact user’s ability and willingness to get directly involved as user’s “involvement willingness”.

To summarize, Connect dimension focuses on the following aspects of users:

- GTBA — users’ non-functional goals

- Importance of these goals based on user’s context

- Users’ involvement willingness (to participate / contribute back)

Connect dimension not only influences company’s brand-related activities but can also be leveraged to evolve company’s products to cater to customer’s GTBA and other non-functional needs of the customers. Moreover, by identifying and focusing on GTBAs, company can deepen the emotional depth of engagement, which, in turn, can help to increase user’s willingness and desire to get involved.

Invite dimension

Frequency of activity and importance of activity are the primary anchors for Engage dimension and Connect dimension, respectively. In both the cases, we consider the usage aspect of the activity. Invite dimension is also dependent on frequency and importance of activity — but from the perspective of selection and making choices. Invite dimension, therefore, depends on frequency of choice and importance of choice (instead of frequency of usage and importance of usage).

In a lot of cases, frequency of choice corresponds to frequency of usage. For example, in on-demand taxi service, one has the choice to select any service provider before every commute. Likewise, customers can choose amongst various food delivery companies at the time of placing an order.

However, products/services with high frequency of usage can have either high or low frequency of choice — depending on whether or not the importance of activity is high or low. For example, a printer can have high frequency of usage but low frequency of choice (one can’t buy a new printer very frequently). On the other hand, products/services with low frequency of usage always have low frequency of choice.

Frequency of choice, in turn, corresponds to demand for the product/service. A product/service with high frequency of choice will have high demand; and vice versa. Demand, of course, depends on the total number of users for the specific product/service as well. For a product/service with a large number of potential customers, a small percentage of users exercising their ability to choose can provide sufficient impetus to a startup to get going.

It is important to note that demand can either be latent or manifested. This depends on whether or not (potential) customers are aware that they can perform their activities in a better way.

If the demand is available (either for the product/service itself or for the category), one can analyze its accessibility across different channels and strive to tap into either the direct demand or into category-specific demand. Each channel has a channel-specific cost and, therefore, has a large impact on the cost-of-customer acquisition and, thereby, the price of the product/service.

If demand is latent and not directly available, the company has to take the ownership to create the category itself. This goes beyond informing the users about availability of solutions; company has to make (potential) customers aware of the problem itself.

This is often done via brand marketing — by identifying specific triggers for the activity (i.e., commonly occurring and highly relatable scenarios) and highlighting that there is a better alternative available. This makes it easier for customers to start visualizing how and when company’s products/services will help them solve their problems. In addition, brand marketing also strives to address the concerns that the customers might have by understanding the barriers to adoption. To connect better with potential customers, brand marketing leverages the “Connect dimension” that we discussed above.

Customers can be made aware of the problem in a product-led way as well: by enabling early adopters to inform their influence networks and social networks while building equity for themselves.

For example, a daily commuter who takes a taxi or bus for the last-mile commute might not be aware of the availability of dockless scooters for the commute. In such cases, it becomes a marketing imperative to create awareness amongst the potential users.

Frequency of choice (latent or manifested) depends not only on the frequency of usage but also on buyer’s ability to switch to a new product. If the product has low switchability, it becomes important to build offerings that help customers to start using the product in addition to the existing products.

Startup’s success depends on the “market readiness” to a large extent — this is because even for categories with low switchability, there are certain moments when it becomes important for companies to bite the bullet and switch to a better (future-ready) solution.

Importance of choice has an implication on the number of stakeholders involved in the selection process. Higher the importance of choice, higher would be the number of stakeholders involved. For B2C products, stakeholders can include family members & friends; for business products, stakeholders can include team members & corporate committees (in addition to the primary buyer, in both cases).

In such cases, it becomes important to not only introduce product/company to the stakeholders via content but also (perhaps more importantly) to build variants of products (what we refer to as “scale products”) that can be evaluated and selected by individual buyers on their own. A classic example of this is the Website Grader product supported by Hubspot, which is a free marketing tool that provides scores based on metrics such as performance, mobile readiness, SEO, and security of the website. Scale products allow users to explore company’s “scale product” offerings (typically aligned with the USPs) with no commitments and, therefore, reduce the effort required for users to familiarize themselves with company and its capabilities.

An important aspect of Invite dimension is customer’s willingness and ability to pay. Customers’ willingness-to-pay depends on the severity of the pain point being faced by customers. The size of the available market opportunity depends on customers’ ability-to-pay (and number of customers who have the ability-to-pay). It is important to understand the acceptable price range from customer’s perspective in order to ensure that the company is able to build the right product and acquire customers using the right channels.

To summarize, Invite dimension focuses on the following aspects of users:

- Importance of choice (esp. stakeholder analysis)

- Frequency of choice (esp. demand availability across channels)

- Customer’s willingness and ability to pay

Category-creating companies often have to operate in a market that does not yet provide direct demand for their products. Product-led thinking and tapping into category-specific demand often helps to create visibility and increase awareness. Importance of choice (including difficulty associated with switching to a new product/service) often constrains company’s ability to tap into the demand. By building scale products that reduce the importance of choice (and, often, increase frequency of choice), this challenge can be alleviated to some extent. In any case, it is important for company’s to understand their target customer’s buyer journey (including defining “firm persona” for business use-cases) in order to ensure that the company’s sales and marketing processes match customer’s buyer journey.

Finally, customer’s ability and willingness to pay are important to understand because they help figure out what price points are needed to drive product adoption.

Summary

Over the last three decades, Apple has introduced innovative products that have radically altered several industries: personal computers, smartphones, tablets, music devices, etc. It has impacted music industry (by enabling switch to music streaming via iTunes), movie industry (via Pixar), and software development industry (by introducing App Store along with the iPhone devices).

How did Apple acquire this stupendous ability to divine what users wanted? Steve Jobs [link] provides us with a clue:

“Some people say, ‘Give the customers what they want.’ But that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I think Henry Ford once said, ‘If I’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me, “A faster horse!”’ People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.”

How can startups “read things that are not yet on the page”? According to Steve Jobs, this is possible by understanding target users deeply and caring deeply about their needs. In Steve Jobs’ words: “Caring deeply about what customers want is much different from continually asking them what they want; it requires intuition and instinct about desires that have not yet formed.” [link]

In order to “read things that are not yet on the page”, companies need to understand not only the functional (unmet) needs of their users but also understand their non-functional needs and desires. Together, JTBD and GTBA enable companies to understand not only “what” kind of products and services they can build but, more importantly, “why” those products / services should be built (based on target customers’ unstated and unfelt needs and wants). The following figure summarizes the salient points of the three dimensions that help build comprehensive 3D view of customers in order to derive customer insights:

A lot of innovative products, however, don’t just serve unmet needs — they also shape new behaviors. New behavior can be shaped only if users think that the company that builds the innovative products understands them. We will like to emphasize the importance between understanding the needs of customers (“Do Goals”) and understanding the customers themselves (“Be Goals”).

If a company understands its target users deeply, it will be able to read things that are not yet on the page and build products that its target users don’t even know that they need.

Also Read:

Entering a New Market as a SaaS Business and Finding First Customers

We’re looking for the next generation of successful Indian marketplaces. If you’re an early-stage marketplace founder, apply now here or learn more about the #DecodingMarketplaces Startup Hunt.

We’d love to hear about your experiences with marketplaces. Let us share our learnings and build a better and stronger ecosystem. Write to us at seedtoscale@accel.com to be a part of the Accel family.

Subscribe to SeedToScale

/subscribe to get the latest stories from SeedToScale/